Indian Express Editorial Analysis

09 March 2021

1. Doubts about new IT rules are groundless

GS 2: Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

GS 3: Role of media and social networking sites in internal security challenges

CONTEXT:

1. The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 establishes a soft-touch, progressive institutional mechanism with a level playing field featuring a code of ethics and a three-tier grievance redressal framework for digital news publishers and OTT platforms.

2. However, some sceptics have described these rules as curbing freedom of expression and have even termed them as dictatorial. They seem to be looking for a black cat in a dark room where none exists.

THREE-TIER GRIEVANCE REDRESSAL FRAMEWORK FOR DIGITAL NEWS PUBLISHERS:

1. It would be required to self-classify their content into five age-based categories — U (Universal), U/A 7+, U/A 13+, U/A 16+, and A (Adult).

2. They would be required to implement parental locks for content classified as U/A 13+ or higher, and reliable age-verification mechanisms for content classified as “A”.

3. Publishers of news on digital media would be required to observe the Norms of Journalistic Conduct of the Press Council of India and the programme code under the Cable Television Networks Regulation) Act, thereby providing a level playing field between the offline (print and television) and digital media.

4. According to the new rules, any person having a grievance regarding the content in relation to the Code of Ethics can file his grievance.

5. Literally, it will force a digital platform to take up any issue by anyone. This opens the floodgates for all kinds of interventions considering the fact that many digital news platforms are small entities.

ISSUE OF CONTENT ON OTT PLATFORMS

1. For the first time in independent India, there is a policy shift from pre-certification or censorship to a more transparent system of self-classification in five different age groups.

2. Self-classification of OTT content is accepted in many countries and there is no question of censorship being imposed on these platforms. The move is to shift to self-classification by creative people themselves.

3. These platforms have very little role in the grievance redressal mechanism. One digital media entity even alleged that the judges on the self-regulation body will be selected from a panel approved by the government.

4. Section 12(2) of the new Rule says on self-regulation: “Section 12(2) — The self-regulatory body referred to in sub-rule (1) shall be headed by a retired judge of the Supreme Court, a High Court, or an independent eminent person from the field of media, broadcasting, entertainment, child rights, human rights or such other relevant field, and have other members, not exceeding six, being experts from the field of media, broadcasting, entertainment, child rights, human rights and such other relevant fields.”

5. Nowhere does the rule talk about any government interference in tier 1 or tier 2 of the self-regulation mechanism, and tier 2 of the self-regulatory body is to be formed by the OTT platforms themselves.

6. The third issue being raised relates to the lack of consultation with OTT platforms. Earlier, the I&B ministry had organised consultations with the platforms on November 10, 2019, in Mumbai and on November 11, 2019, in Chennai.

7. OTT platforms have been having discussions with the ministry for a long time but they must realise that consultation does not mean concurrence.

8. As regards digital news portals, the requirement placed on them is to follow the established journalistic codes. They also have to ensure that prohibited content, such as child pornography, is not transmitted.

HOW DOES A CODE OF CONDUCT AMOUNT TO CURBING THE FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION?

-

The new rules will also regulate digital news media, it is a prime source of news. Any government involvement could have a chilling effect on their free speech and conversations.

-

Digital news portals should introspect on why they did not develop their own code for so long.

-

Another requirement being placed on digital news portals is regarding the furnishing of basic information and the grievance redressal mechanism.

-

It is surprising that many portals, particularly at the state/district level, do not wish to give common citizens any opportunity to email them, in case they have a grievance.

-

It is quite surprising that those who talk about transparency are non-transparent in their own actions.

-

Some senior journalists have also raised misgivings regarding Rule 16 under Part III of the rules, which says that in an emergency situation, interim blocking directions may be issued by the secretary, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

-

This is exactly the same provision being used by the secretary, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology for the past 11 years under the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009.

-

Part III of the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, would be administered by the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting.

-

That is the reason the reference to the MeitY secretary has been replaced by secretary, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting and no new provision has been made. This provision is made for emergency situations and has to be ratified within 48 hours.

-

Moreover, new rules have increased the censorship of Internet content. It mandates compliance with government demands regarding user data collection and policing of online services in India.

OTT CLASSIFICATION IN DIFFERENT COUNTRIES:

1. In Singapore, the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), established under the Broadcasting Act, 1994, is the common media regulatory body for different media.

2. The country has adopted a licencing model where service providers are required to obtain a licence for operation.

3. A content code for OTT, video-on-demand and niche services is in effect from March 1, 2018, and provides, inter alia, for classification of content, parental lock and age verification, display of rating and content elements and specific provisions for news, current affairs and educational programmes.

4. To aid parental guidance and allow for informed viewing choices, all content in Singapore must be rated according to the Film Classification Guidelines.

5. The six ratings are G (general), PG (parental guidance), PG13 (parental guidance for children below 13 years), NC16 (no children below 16 years), M18 (mature 18, for persons of 18 years and above) and R21(restricted to persons of 21 years and above).

6. In Australia, online media is regulated through the Broadcasting Services Act, 1992, read together with the Enhancing Online Safety Act 2015. For matters related to online safety (including digital media), the office of the eSafety Commissioner is the regulatory authority.

7. The Broadcasting Services Act, 1992 has provisions for classification of content, restricted access to certain kinds of content, industry codes and industry standards, complaint mechanism, etc.

8. However, in Australia, classifications are advisory categories. This means there are no legal restrictions regarding viewing and/or playing these categories — general (G), parental guidance (PG) and mature (M).

9. In the United Kingdom, the Office of Communications (Ofcom) and the Communications Act, 2003 regulate the communications landscape.

10. The UK Government released a white paper on the threats posed by unregulated online content.

11. The paper has proposed a new independent regulator to ensure online safety; develop codes of practice, impose liabilities/fines on companies, and coordinate with law enforcement agencies.

WAY FORWARD:

Given the new challenges in digital content, some strict policy measures are needed. However, the centre decision to involve in the grievance redressal process as an apex body cannot solve these problems.

Also, over-regulation will prove counterproductive in a country where the citizens still do not have a data privacy law.

CONCLUSION:

The apprehensions being expressed by sceptics seem groundless. Let all those who are searching for “something in the dark room” open the doors and windows to allow in some light; the search would become easier.

2. Make room for women in the new normal

GS 1: Social Empowerment

Role of Women

CONTEXT:

1. Even before mask-wearing limited our ability to connect with the external world, it was commonplace for 60 per cent of Indian women who practise either the ghunghat or purdah.

2. The telephone was already the lifeline connecting women to their support network — about a quarter of women respondents were unable to visit their natal families more than once a year.

3. Part of this isolation may be because it is difficult for women to travel unless someone accompanies them.

STATISTICS ON WOMEN’S LACK OF ACCESS TO PUBLIC SPACES ARE SOBERING

-

The India Human Development Survey of 2012 (IHDS), conducted by the University of Maryland and National Council of Applied Economic Research, revealed that 18 per cent of women respondents do not go to a kirana shop. A further 19 per cent would not go alone.

-

A third of households relied only on men or children to do any grocery shopping. Only 11 per cent of rural women had ever attended a gram sabha.

-

Barely 18 per cent had ever visited a metropolitan city, and an equal proportion had ventured outside their state.

ISSUES:

1. Perhaps the pandemic-enforced isolation will increase our empathy for the substantial proportion of Indian women who have found themselves confined to their homes during the normal course of life. The challenge, however, lies in understanding what has caused this isolation and finding ways to address it.

2. A large number of studies have documented that women face sexual harassment as they venture outside the home. Fear of sexual harassment has negative societal consequences in many areas of life.

3. Women are less likely to work away from home in areas where perceived sexual harassment of girls is higher. Despite having high marks, girls in Delhi University choose to attend lower-quality colleges to avoid sexual harassment while traveling to college.

4. Safety concerns are not limited to major metropolitan cities. A study carried out by the NGO Safetipin in Bhopal, Gwalior and Jodhpur found that 95 per cent of women feel unsafe using public transport, 89 per cent feel unsafe in the marketplace, 84 per cent feel unsafe waiting for public transport while 76 per cent feel unsafe on roads or footpath.

5. The study found that about 30 per cent of women reported having faced some form of sexual harassment in the past year. Half of these incidents took place while using public transport and 16 per cent were while waiting for public transport.

WHAT CAN BE DONE TO ENHANCE WOMEN’S FEELING OF SAFETY AND TO ENSURE THEIR FULL PARTICIPATION IN PUBLIC LIFE?

1. Some of these are relatively simple — improving lighting around roads, buses, and train stations is relatively simple.

2. However, we also need to look to more creative solutions to create a critical mass of women in public spaces so that women don’t feel isolated and see safety in numbers.

3. This may involve hiring women drivers and bus conductors, emulating Lahore’s pink buses, and expanding spaces allocated to women vendors in markets.

4. It also involves creating an environment where the whole society collaborates to welcome women into public life. This is not a one-way street, benefitting women alone.

5. The Indian Independence movement offers an inspirational example of the synergy between the women’s movement and the nationalist movement.

6. This intertwining won freedom for the nation while creating an obligation for an Independent India to deliver gender justice, resulting in the Hindu Code Bill that provided for monogamy, divorce, and inheritance rights for women.

7. MGNREGA, with equal pay for men and women, has played an important role in bringing women, who used to work only on family farms in the past, into paid work.

8. Finding opportunities for women to participate in creating public goods, whether through special programmes designed for women or structuring existing programmes in a way that allows for enhanced participation by women can only be a win-win situation.

CONCLUSION:

1. The COVID-19 pandemic has made it clearer than ever that women’s unpaid domestic labour is subsidising both public services and private profits.

2. This work must be included in economic metrics and decision-making. We will all gain from working arrangements that recognise people’s caring responsibilities, and from inclusive economic models that value work at home.

3. This pandemic has not only challenged global health systems, but our commitment to equality and human dignity.

4. Let us hope that when we tell our grandchildren about 2020, the pandemic generated isolation is as unfamiliar to our granddaughters as to our grandsons, and the reclaiming of public spaces occurs for both men and women.

3. The real victims of nativist labour laws? Low-income migrant workers

GS 2: HUMAN RESOURCE.

CONTEXT:

1. Political rhetoric and the occasional violence against inter-state migrant workers is nothing new in India.

2. Starting from the Mulki rules in Nizam-ruled Hyderabad in the late 19th century that favoured local employment to the anti-South Indian movements in Bombay in the 1960s (when this writer’s family surname was changed to fit in with the locals) to the “sons of the soil” movement in Assam and beyond, India has witnessed many instances of subnational nativism.

Internal Migrants:

1. These are migrants who within a country

2. Internal migrants in India are a vast and heterogeneous population.

3. They are of three traits: they predominantly migrate from villages to cities; they are low-income populations who work in the informal sector; they have not permanently relocated their families to the city. Instead, they circulate between villages and cities several times a year.

BACKGROUND:

1. This nativism peaked in times of high unemployment and withered away when the economy did well.

2. Nativist rhetoric also rarely transcended into actual laws in India as they remained in the realm of pre-election vote-catching banter.

3. After all, several Articles of the Indian Constitution prohibit discrimination in employment on the basis of place of birth.

4. As pointed out by the report of the Working Group on Migration in January 2017, the Supreme Court decision in 2014 in the Charu Khurana v Union of India case “clearly renders restrictions based on residence for the purposes of employment unconstitutional.”

LEGISLATIVE REALITY:

1. In 2019, the government of Andhra Pradesh passed the Andhra Pradesh Employment of Local Candidates in the Industries/Factories Bill, 2019, reserving 75 per cent of jobs for locals.

2. This law was soon challenged and the petition was accepted by the Andhra Pradesh High Court as a matter of public interest.

3. Yet, the clamour for similar laws pervades across states including Madhya Pradesh and Goa. Most recently, in March, the Haryana government passed the Haryana State Employment of Local Candidates Bill, 2020, reserving 75 per cent of jobs in the private sector for locals, when the monthly salary was under Rs 50,000 per month.

4. The fundamental problem with this law is that low-income migrant workers will once again become the victims of India’s public policies.

ISSUES:

1. Life is tough for low-income inter-state migrant workers in India, as was painfully illustrated by the migration crisis of 2020. To their long list of woes, ranging from precarious livelihoods to lack of access to portable social security, they now have an added source of concern — nativist laws.

2. Sectors which do end up employing a large number of inter-state migrant workers — think of Surat’s power loom industry which employs workers from Odisha — do so because the local workers do not aspire for those jobs.

3. Migration for work represents a match between employers who are looking for certain skills at low rates and workers who want to earn much more than what they can make back home.

4. The current premise of the nativist laws is that with adequate skill training given to locals, they can perform the same tasks as the migrants.

5. The law also appears to be tough to implement on the ground and one can expect a parallel market to emerge on the ability to prove local residence, as it often happens in the case of ration cards.

6. Further, the income cut-off in Haryana’s law conveys that the rich can move anywhere in India and work as they please but those same opportunities are to be denied to poorer inter-state migrant workers.

WAY AHEAD:

1. Recognition of circular migrants as part of India’s urban population.

2. Relaxing the restrictions that prevent migrants from accessing vital benefits

3. Prioritising dedicated transport options for migrants to prevent overcrowding.

4. Special Measures should also take into account the particular situation of migrant women.

CONCLUSION:

1. In the coming decades, internal migration is only going to continue to surge in India, as it did in China over the past three decades, and as it did in the developmental trajectory of practically every country on this planet.

2. By restricting migration choices, the governments of Andhra Pradesh and Haryana send out bad signals in the labour market, especially when their own elites have benefited tremendously from internal and international migration.

3. Haryana’s nativist law alas will not “Make Haryana Great Again”. Instead, it sows the seeds of the balkanisation of our country. Such laws ought to be challenged in the courts.

-

Public or private? The future of banking in India and US

GS 3: Indian Economy and issues related to planning

CONTEXT:

-

One cannot but be struck by the apparent irony in recent banking system trends in India and the United States. Spurred by a lack of financial inclusion, a public banking movement is rapidly gaining traction in the United States, a bastion of free markets.

-

In contrast, India, a prime example of state intervention and government-owned-bank dominance, seems to be quickly warming to the idea of bank privatisation.

BACKGROUND:

-

The debate on the benefits and costs of public versus private banks is not new. Dating back to Alexander Gerschenkron in 1962, the development view sees government presence in the banking sector as a means to overcome market failures in the early stages of economic development.

-

The core idea is that government-owned banks can improve welfare by allocating scarce capital to socially productive uses.

-

By contrast, the political view argues that vested interests can commandeer the lending apparatus to achieve political goals. Political or special interest capture can distort credit allocation and reduce allocative efficiency in government-owned banking systems.

-

Persuaded by the evidence that government ownership in the banking sector leads to lower levels of financial development and growth, waves of banking sector privatisations swept across emerging markets in the 1990s.

-

The policymaker consensus saw bank privatisation as an efficient means to achieve economic and financial development.

-

Indeed, cross-country evidence suggests that bank privatisations improved both bank efficiency and profitability — specifically, increasing solvency and liquidity whilst reducing troubled or non-performing assets. India is, therefore, somewhat late to the game.

PRIVATE BANKING MODEL:

-

Public sector Banks (PSBs) dominate Indian banking, controlling over 60 per cent of banking assets.

-

The private-credit to GDP ratio, a key measure of credit flow, stands at 50 per cent, much lower than international benchmarks — in the US it is 190 per cent, in the UK 130 per cent, in China 150 and in South Korea it is 150 per cent. The quality of credit is problematic as well.

-

India’s Gross NPA ratio was 8.2 per cent in March 2020, with striking differences across PSBs (10.3 per cent) and private banks (5.5 per cent).

-

The end result is much lower PSB profitability compared to private banks. Clearly, the rationale for privatisation stems from these considerations.

-

While the United States epitomises the private banking model, a nationwide public banking movement is coming into vogue —this includes recently introduced state bills from California to New York.

-

If modelled along the lines of the Bank of North Dakota, America’s only public bank, reports suggest that public banks can contribute to state revenues, support community banks, fund public infrastructure projects, and help small businesses grow by offering lower interest rates and lower fees.

-

The public banking movement can also help with efficient government transfers and financial inclusion via universal checking accounts.

-

According to pre-pandemic data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), 5.4 per cent of the households in the United States are unbanked. India is no stranger to the imperative for digital financial inclusion.

-

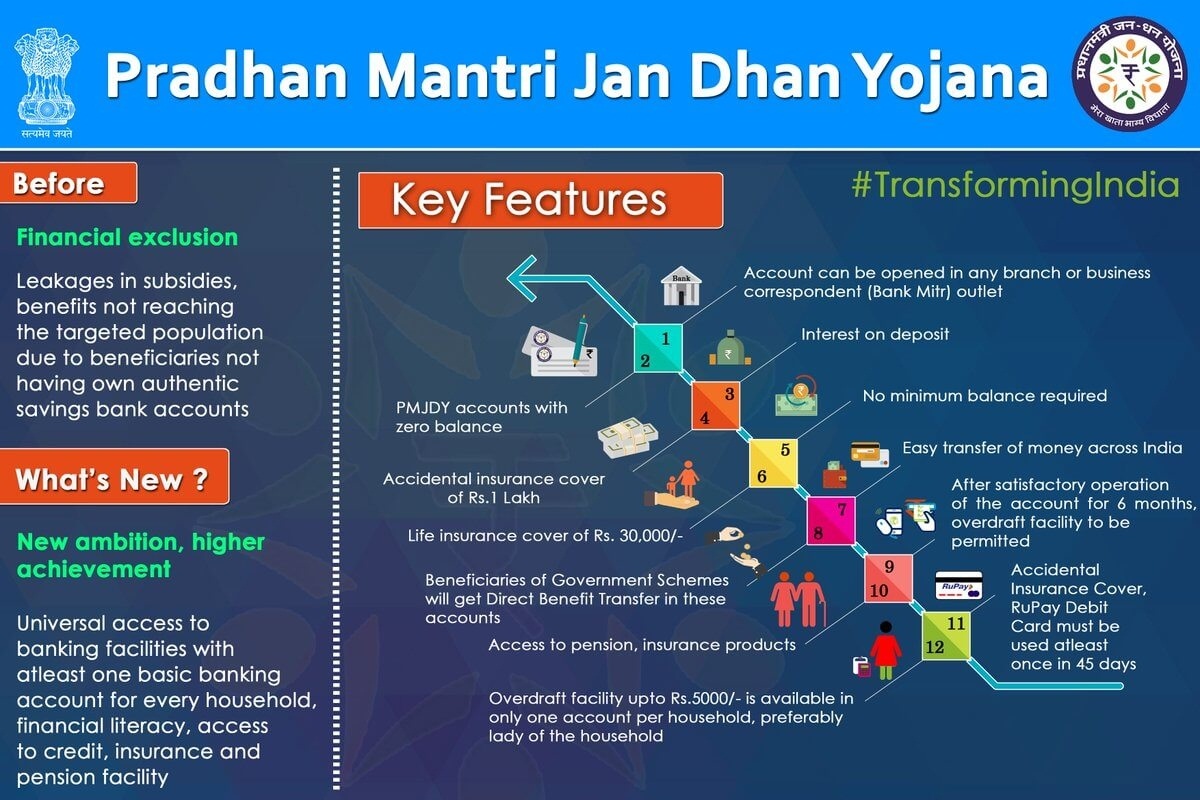

The Jana Dhan Yojna (PMJDY) is a flagship scheme designed to overcome slippages in delivering transfer payments to ultimate beneficiaries. The programme is administered primarily through government-owned banks.

PUBLIC GOOD VS CREDIT ALLOCATION:

-

The stellar success of Indian PSBs in implementing the PMJDY while missing the mark on creating high-quality credit highlights a critical divide between the asset and the liability side of a bank.

-

Banks provide two functions at a fundamental level: Payments and deposit-taking on the liability side and credit creation on the asset side.

-

The payment services function, a hallmark of financial inclusion, is similar to a utility business — banks can provide this service, a public good, at a low cost universally. The lending side, in contrast, is all about the optimal allocation of resources through better credit evaluation and monitoring of borrowers.

-

Private banks are more likely to have the right set of incentives and expertise in doing so. It comes as no surprise that the PSBs in India are better at providing the public good functions, whereas private banks seem better suited for credit allocation.

CONCLUSION:

-

The optimal mix of the banking system across public and private boils down to what you need out of your banking system and the particular friction your economy faces.

-

When the wedge between social and private benefits is large, as with financial inclusion, there is a strong case for public banks.

-

At this stage, inefficiency in capital allocation seems to be a bigger issue for the Indian banking sector, whereas, in the US, the debate is centred around the public goods aspects of banking.

-

Therefore, it may make sense for the US to think hard about public banks that can be used for financial inclusion in line with the success of PMJDY in India. On the other hand, selective privatisation of inefficient PSBs is a welcome move for India’s banking sector.